Lifestyle modification for improving anxiety and depression among patients with irritable bowel syndrome

Seyed Shahab Banihashem1, Afrooz Ahmadi Ghadikolaee2, Amir Sadeghi2, Reyhaneh Rastegar2, Mona Mirzaei2, Forough Yousefi Saber1

+ Affiliation

Summary

Objective: The aim of this study was to evaluate the beneficial effects of lifestyle modification and dietary intervention on the severity of symptoms, quality of life, anxiety and depression status in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Methods: In this clinical interventional trial study, patients aged 15 to 65 years with IBS (based on the ROME IV criteria) who were referred to the gastrointestinal clinic of Taleghani hospital, Tehran, Iran between March 2020 and August 2020 were included. After initial evaluation, lifestyle modification intervention was performed. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. Results: In the present study, 55 patients consisting in 27 men and 28 women with IBS were included. The patients‘ mean anxiety score (based on BAI) and mean depression score (based on BDI) were significantly reduced after lifestyle and diet modification intervention as compared to the baseline. The mean score of the patients‘ quality of life (based on IBS-QOL) was 68.36 ±24.90 before the intervention, which increased to 82.75 ±29.52 after the intervention, indicating a significant difference (P <0.001). Similarly, the mean score of severity of IBS symptoms (based on IBS-SSS) was 28.29 ±8.27 before the intervention, which was reduced to 20.87 ±8.47 after the intervention with a significant difference (P <0.001). Conclusion: Our findings suggest that lifestyle and dietary modification might be a feasible and effective treatment approach in patients with IBS, which has a positive and significant effect on amelioration of the severity of symptoms, improving the quality of life as well as alleviating symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Keywords

irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, depression, quality of life, lifestyle modification

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional disorder of the large intestine [1]. The tenth version of ICD classifies it as a functional disorder and the eleventh version as a physical stress disorder. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome can have a variety of symptoms such as distention, bloating and abdominal pain, as well as changes in bowel habits such as constipation or diarrhoea [2]. The prevalence of IBS varies between 1% and 45% – probably due to the use of different diagnostic criteria. Its global average prevalence is 11.2% [3], which reflects its 10% to 20% prevalence in Western countries [4]. We can diagnose IBS worldwide using Roman criteria (last revised in 2016 and renamed Rome IV). These criteria are for patients who have had recurrent abdominal pain at least once a week for the past 3 months [5]. In addition, it is necessary to consider two of the following three criteria: [1] these complaints are related to defecation [2], the frequency of defecation changes and [3] the consistency of the stool changes [2]. According to Roman IV criteria, IBS can fall into four different subgroups. IBS-D (diarrhoea): More than 25% of the stool is liquid and has no solid components, less than 25% of which are solid components. IBS-C (constipation): More than 25% of the stool contains separate solid pieces and less than 25% of which is liquid and has no solid components. IBS-M (mixture): More than 25% of the stool is liquid and has no solid components and more than 25% of the stool contains separate solid pieces. IBS-U (unclassified): the components are not fully assignable [2]. Although the pathophysiology of IBS is not yet fully knowable, several factors appear to be involved in its pathogenesis, including biological, environmental, psychosocial and genetic factors. Lifestyle-related factors such as nutrition, physical activity and stress play a major role in the development of IBS [6–8]. Observational studies have shown that certain food groups such as wheat-based cereals, dairy products, fatty, spicy and processed foods, coffee and alcohol, and low consumption of vegetables, legumes and fruits may be associated with IBS symptoms [9–12]. Moreover, irregular eating patterns and not eating the main meals are associated with IBS [10,13]. One of the strongest risk factors of developing IBS is acute infectious gastroenteritis including viral, bacterial and protozoal gastroenteritis. This condition is called post-infection IBS. Intolerance to oligo, di- and monosaccharides, polyols (FODMAPs) and gluten can also mimic the symptoms of IBS, 21 discoveries that led to a diet with low FODMAP [14,15]. In addition, soluble fibre is supposedly effective in treating IBS patients, especially those with constipation [16]. In contrast, insoluble fibre can exacerbate the symptoms of IBS [17]. Although probiotics have been effective in treating IBS [18], the effects of some specific strains have not been well provable [16]. Several studies have reported that high physical activity is effective in improving IBS symptoms [8,19,20]. While smoking is also recognised as a contributing factor in creating IBS [21], the association between smoking and IBS is controversial. [22] Some psychological characteristics, especially distraction, depression, anxiety and somatisation are strongly associated with IBS [10,13,23,24]. This study evaluates the positive effects of lifestyle modification and dietary change on the severity of symptoms, quality of life, anxiety and depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

Methods

In this clinical interventional trial study, patients aged 15 to 65 years with IBS (based on the ROME IV criteria) who were referred to the gastrointestinal clinic of Taleghani Hospital, Tehran, Iran between March 2020 and August 2020 were included. Patients undergoing psychiatric treatment and those who did not follow the study treatment protocol were excluded from our intervention. Following the collection of baseline characteristics including demographics, medical history, socioeconomic data, history of smoking or alcohol use, physical activity and nutritional habits, the patients were assessed by the following questionnaires: 1. IBS-SSS: this 5-question survey measures the severity of IBS including abdominal pain, frequency of abdominal pain, severity of abdominal distention, dissatisfaction with bowel habits and interference with quality of life over the past 10 days. 2. IBS-QOL: This scale measures the level of quality of life. The participant’s responses to the 34 items are summed and averaged for a total score. There are also eight subscale scores for the IBS-QOL (Dysphoria, Interference with Activity, Body Image, Health Worry, Food Avoidance, Social Reaction, Sexual, Relationships). 3. Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI): this self-report 21-question questionnaire evaluates the anxiety status. The questions measure common symptoms of anxiety that participants experienced during the past week (including the day of taking it) (such as numbness and tingling, sweating not due to heat and fear of the worst happening). The BAI contains 21 questions, each answer being scored on a scale value of 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely); higher total scores indicate more severe anxiety symptoms. 4. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI): the depression status was evaluated by the BDI, which is a 21-question multiple-choice self-report inventory. The value of every item in between 0–3 and a high score shows high depression.

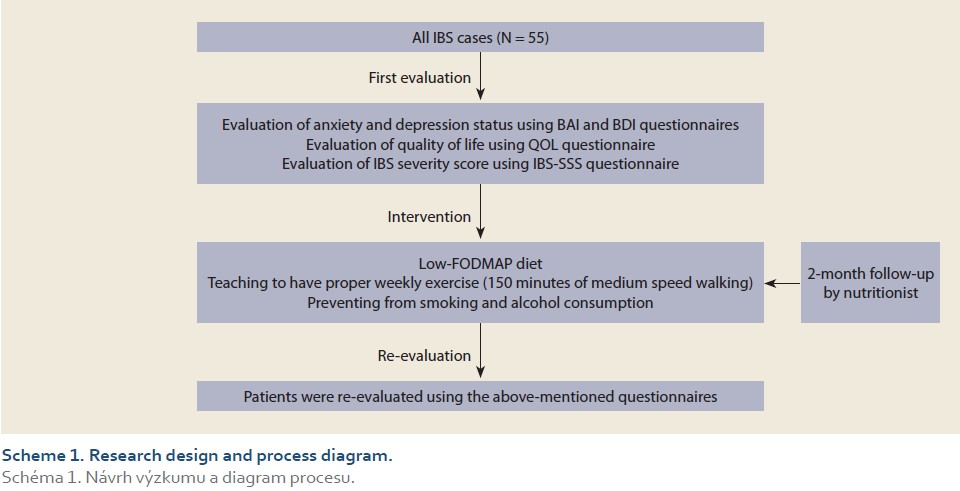

After initial evaluation, lifestyle modification intervention was performed. (Interventions include: Adequate physical activity training as 150 minutes per week – medium speed walking – no smoking or alcohol, and low-FODMAP diet by nutrition and psychology consultants). After an intervention period of 2 months, patients who complied with the statement of a first-degree family member who followed the low-FODMAP lifestyle modification intervention were re-evaluated with the above questionnaires. The exercise protocol was taught by a particular brochure and pamphlets. We also had some experts whom the patients could contact in case of any questions. Since all of the patients joined this study group as volunteers they were truly motivated themselves and there was no need for us to provide motivation for them

The study endpoint was to evaluate the effect of intervention on quality of life, anxiety and depression in these patients (Scheme 1). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (ethical code: IR.sbmu.msp.rec.1397.333).

For statistical analysis, the results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables and were summarised by frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. To assess the change in scores of the study quantitative parameters, a paired t test or Wilcoxon test was employed. P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the statistical analysis, the statistical software SPSS version 23.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, New York) was used.

Results

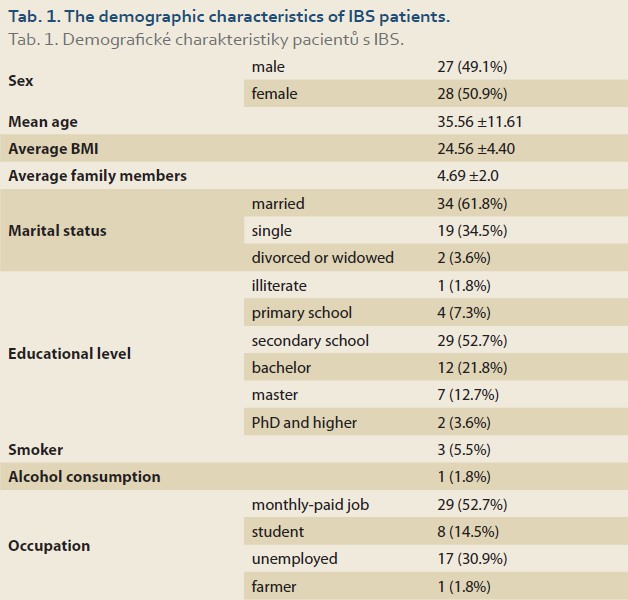

In the present study, 55 patients consisting of 27 men and 28 women with IBS were included. The mean age of patients was 35.56 ±11.61 years, ranging from 15 to 65 years. The mean BMI and the mean number of family members were 24.56 ±4.40 and 4.69 ±2.0, respectively. Most of the patients included were married (61.8%), had completed their secondary school education (52.7%) and had a monthly paid job (52.7%). The complete data regarding the general characteristics of patients is provided in Tab. 1.

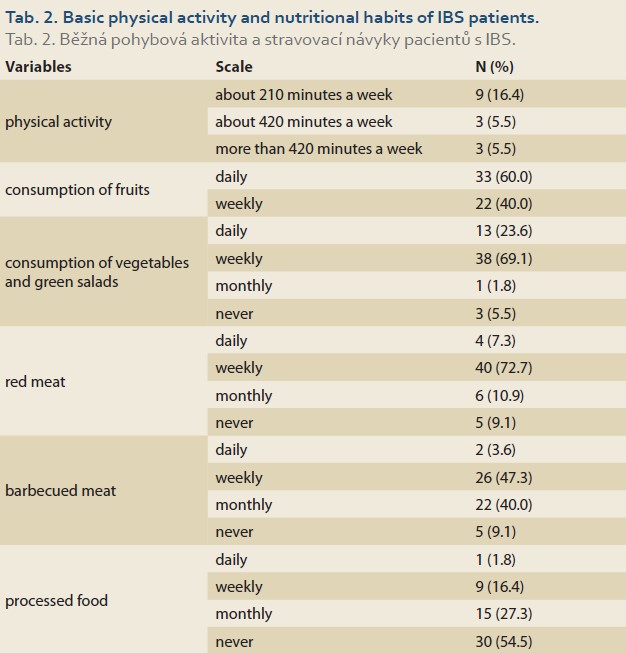

Tab. 2 summarised the basic physical activity and nutritional habits of the patients. On the first evaluation only 27.4% of our patients reported regular weekly exercise, 16.4% of which were about 210 minutes per week. Daily consumption of fruits and vegetables was recorded in 60% and 23.6% of the included patients. Most of the patients mentioned the weekly use of red (72.7%) and barbecued (47.3%) meat in their routine diet. The majority of the patients also declared that they did not routinely eat any processed food (54.5%)

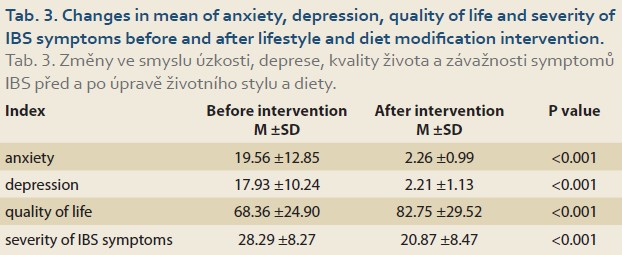

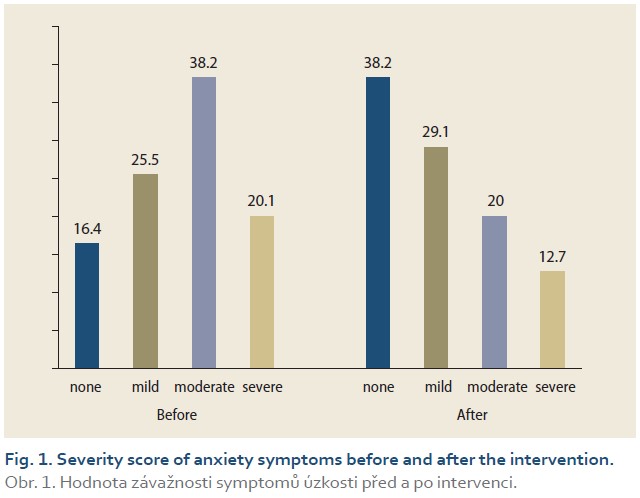

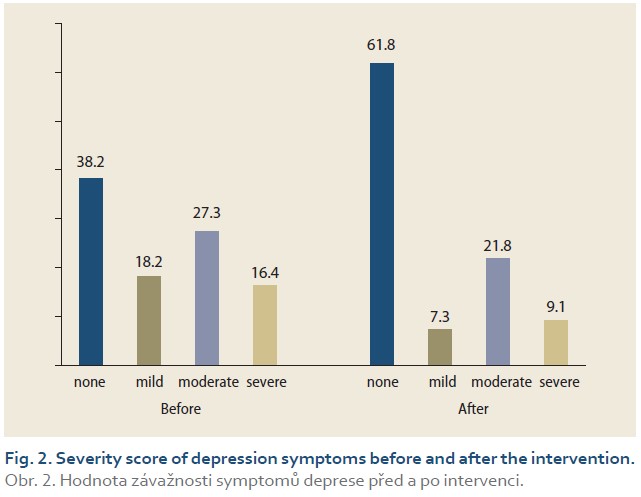

As shown in Tab. 3, the patients‘ mean anxiety score (based on BAI) and mean depression score (based on BDI) significantly reduced after lifestyle and diet modification intervention as compared to the baseline. In this regard, the frequency of severe anxiety before and after intervention was 20.0% and 12.7%, respectively, while the prevalence of depression was also 16.4% and 9.1%, respectively (Fig. 1, 2). The mean score of the patients‘ quality of life (based on IBS-QOL) was 68.36 ±24.90 before the intervention, which increased to 82.75 ±29.52 after the intervention, indicating a significant difference (P <0.001). Similarly, the mean score of severity of IBS symptoms (based on IBS-SSS) was 28.29 ±8.27 before the intervention, which was reduced to 20.87 ±8.47 after the intervention with a significant difference (P <0.001).

Discussion

The first common treatment option is lifestyle modification. These modifications include regular exercise, reducing the beverage intake, changing the diet, avoiding alcohol and coffee and regulating sleep. In most cases, physical activity has been an initial treatment for IBS patients. This results from the studies examining the benefits of physical activity for IBS. Recently, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving 102 patients with IBS proved that people belonging to the physical activity group showed fewer symptoms of IBS than those in the control group [25]. This is consistent with our results on the significant reduction in the severity of symptoms after lifestyle modification. Other studies have also shown that physical activity can improve the patient‘s mood and symptoms of fatigue, bloating and abdominal pain. Regular physical activity can improve bowel movements in patients with chronic constipation [26–28].

On the other hand, our results were consistent with a meta-analysis of seven RCTs involving adults with IBS, as they showed that low-FODMAP diets were associated with reduced overall symptoms of IBS compared to control diets (alternative diets, high-FODMAP diets, daily diets or placebos). The persistence of IBS symptoms was 43.2% vs. 61.6%, respectively, and RR = 0.7, 95% CI: 0.5– –0.9) [29]. In an RCT conducted by Zahedi et al, after 6 weeks patients with IBS-D randomly assigned to a low-FODMAP diet (55 people) observed an improvement in abdominal pain intensity (P = 0.001), frequency of pain (P = 0.02), abdominal distention (P <0.001), dissatisfaction with intestinal function (P = 0.001) and interference with daily life (P = 0.005) [30]. Moreover, a diet with low-FODMAP compared to the modified diet (recommended by the National Institutes of Health and Care Excellence) during a 4-week RCT on 84 patients with IBS-D (Aswaran et al) improved the baseline quality of life scores [31]. A higher percentage of patients on a diet with low-FODMAP after 4 weeks (52% vs. 21%, respectively; 95% CI: –0.52 to –0.08) received a clinical response (i.e. at least a 14% improvement in the baseline score of quality of life) [31]. Taken together, these data suggest that following a low-FODMAP diet may be a reasonable dietary approach for patients with IBS-D. Although there is no definitive treatment plan for IBS-D, this is often the first intervention by primary care providers and gastroenterologists. In addition, we should note that many gluten-containing foods with high-FODMAP are in consideration. The prevalence of anxiety (23%) and depressive disorders (23.3%) in IBS patients has been considerable as reported. Moreover, researchers have found that patients with IBS are prone to comorbid psychiatric disorders compared to those in the control group [32]. Recently, a meta-analysis found that IBS patients with symptoms of constipation had the highest rates of depression (38%) and anxiety (40%).

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends less exercise for the treatment of IBS symptoms, although this recommendation is based on limited data and appropriate clinical trials are necessary [33]. A meta-analysis of various types of exercise (such as yoga, walking, cycling, swimming and running) reported improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms, quality of life and anxiety in patients with IBS (683 patients). These studies differed in terms of patient demographic characteristics, study design and size, and limit the generalisation of results [34]. Our study showed a significant improvement in quality of life and the severity of IBS symptoms, as well as anxiety and depression scores. In this study, several mechanisms may help improve the patients‘ symptom severity and quality of life after regular exercise. Physical and psychological factors are probably influential. The role of physical factors may be that due to increased physical activity, increased gas and faeces are discharged from the intestines, which may be associated with improved IBS symptoms [35]. Dainese et al (2004) showed that moderate physical activity reduced gas discharge time and abdominal distention in healthy individuals [36]. Intestinal-brain interaction may also be a psychological factor in the results of the current study. Thus, stress intensifies the neuroendocrine response and visceral perception [37], while physical activity neutralises the effects of stress [38]. By facilitating the production, adaptation and protective processes of the central nervous system, physical activity may have a positive effect on the gut-brain axis involved in IBS [38]. On the other hand, increased cardiopulmonary capacity and physical activity lead to less depression and more happiness [39]. Physical activity supposedly reduces the visceral blood flow, increases gastrointestinal motility, strengthens the immune system and compresses the gut [40]. Some studies have also shown that physical activity reduces bowel discharge time and eliminates incomplete bowel movements in patients with chronic constipation [41], which is a common symptom in IBS [42]. Therefore, the results of the current study are reasonable; they show an improvement in quality of life and symptom severity in patients with IBS after aerobic exercise.

Our study had some limitations, such as the low number of participants. On the other hand, our study included no control group.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that lifestyle and dietary modification might be a feasible and effective treatment approach in patients with IBS, which has a positive and significant effect on amelioration of the severity of the symptoms, improving the quality of life as well as alleviating symptoms of anxiety and depression.

ORCID authors

A. Ahmadi Ghadikolaee ORCID 0000-0002-4629-5292,

A. Sadeghi ORCID 0000-0002-9580-26.

Submitted/Doručeno: 12. 2. 2022

Accepted/Přijato: 26. 4. 2022

Amir Sadeghi, MD

Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases research center

Taleghani Hospital, Shahid

Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

30stana@gmail.com

To read this article in full, please register for free on this website.

Benefits for subscribers

Benefits for logged users

Literature

1. Březina J, Bajer L, Špičák J. Fekální mikrobiální transplantace u idiopatických střevních zánětů. Gastroent Hepatol 2016; 70(1): 51–56. doi: 10.14735/amko201651.

2. Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1393–1407. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031.

3. Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2: 16014. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.14.

4. Thompson WG. The treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16(8): 1395–1406. doi: 10.1046/j.1365 2036.2002.01312.x.

5. Lacy BE, Patel NK. Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Med 2017; 6(11): 99. doi: 10.3390/jcm 6110099.

6. Furnari M, de Bortoli N, Martinucci I et al. Optimal managementof constipation associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2015; 11: 691–703. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S54298.

7. Khayyatzadeh SS, Kazemi-Bajestani SMR, Mirmousavi SJ et al. Dietary behaviors in relation to prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescent girls. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 33(2): 404–410. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13908.

8. Sadeghian M, Sadeghi O, Hassanzadeh Keshteli A et al. Physical activity in relation to irritable bowel syndrome among Iranian adults. PLoS One 2018; 13(10): e0205806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205806.

9. Esmaillzadeh A, Keshteli AH, Hajishafiee M et al. Consumption of spicy foods and the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(38): 6465–6471. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i38.6465.

10. Okami Y, Kato T, Nin G et al. Lifestyle and psychological factors related to irritable bowel syndrome in nursing and medical school students. J Gastroenterol 2011; 46(12): 1403–1410. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0454-2.

11. Rajilić-Stojanović M, Jonkers DM, Salonen A et al. Intestinal microbiota and diet in IBS: causes, consequences, or epiphenomena? Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110(2): 278–287. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.427.

12. Nilholm C, Larsson E, Roth B et al. Irregular dietary habits with a high intake of cereals and sweets are associated with more severe gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS patients. Nutrients 2019; 11(6): 1279. doi: 10.3390/nu11061279.

13. Miwa H. Life style in persons with functional gastrointestinal disorders – large-scale internet survey of lifestyle in Japan. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012; 24(5): 464–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01872.x.

14. Mansueto P, Seidita A, D‘Alcamo A et al. Role of FODMAPs in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr Clin Pract 2015; 30(5): 665–682. doi: 10.1177/0884533615569886.

15. Berumen A, Edwinson AL, Grover M. Post-infection irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2021; 50(2): 445-461. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2021.02.007.

16. Heizer WD, Southern S, McGovern S. The role of diet in symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a narrative review. J Am Diet Assoc 2009; 109(7): 1204–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.04.012.

17. Moayyedi P, Quigley EM, Lacy BE et al. The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109(9): 1367–1374. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.195.

18. Whelan K, Quigley EM. Probiotics in the management of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2013; 29(2): 184–189. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835d7bba.

19. Asare F, Storsrud S, Simren M. Meditation over medication for irritable bowel syndrome? On exercise and alternative treatments forirritable bowel syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2012; 14(4): 283–289. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0268-2.

20. Johannesson E, Ringstrom G, Abrahamsson H et al. Intervention to increase physical activity in irritable bowel syndrome showslong-term positive effects. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(2): 600–608. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i2.600.

21. Han SH, Lee OY, Bae SC et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Korea: population-based survey using the Rome II criteria. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 21(11): 1687–1692. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04269.x.

22. Kubo M, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M et al. Differences between risk factors among irritable bowel syndrome subtypes in Japanese adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 23(3): 249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01640.x.

23. Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, Zinsmeister AR et al. Psychosocial distress and somatic symptoms in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: a psychological component is the rule. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104(7): 1772–1779. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.239.

24. van Tilburg MA, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Which psychological factors exacerbate irritable bowel syndrome? Development of a comprehensive model. J Psychosom Res 2013; 74(6): 486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.03.004.

25. Grundmann O, Yoon SL. Complementary and alternative medicines in irritable bowel syndrome: an integrative view. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(2): 346–362. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.346.

26. Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H et al. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106(5): 915–922. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.480.

27. Yoon SL, Grundmann O, Koepp L et al. Management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in adults: conventional and complementary/alternative approaches. Altern Med Rev 2011; 16(2): 134–151.

28. De Schryver AM, Keulemans YC, Peters HP et al. Effects of regular physical activity on defecation pattern in middleaged patients complaining of chronic constipation. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40(4): 422–429. doi: 10.1080/00365520510011641.

29. Dionne J, Ford AC, Yuan Y et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy of a gluten-free diet and a low FODMAPs diet in treating symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113(9): 1290–1300. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0195-4.

30. Zahedi MJ, Behrouz V, Azimi M. Low fermentable oligo-di-mono-saccharides and polyols diet versus general dietary advice in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 33(6): 1192–1199. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14051.

31. Eswaran S, Chey WD, Jackson K et al. A diet low in fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols improves quality of life and reduces activity impairment in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15(12): 1890–1899. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.044.

32. Zamani M, Alizadeh‐Tabari S, Zamani V. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019; 50(2): 132–143. doi: 10.1111/apt.15325.

33. Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Chey WD et al. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113(Suppl 2): 1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0084-x.

34. Zhou C, Zhao E, Li Y et al. Exercise therapy of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018; 31(2): e13461. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13461.

35. Johannesson E, Ringstrom G, Abrahamsson H et al. Intervention to increase physical activity in irritable bowel syndrome shows long-term positive effects. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(2): 600–608. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i2.600.

36. Dainese R, Serra J, Azpiroz F et al. Effects of physical activity on intestinal gas transit and evacuation in healthy subjects. Am J Med 2004; 116(8): 536–539. doi: 10.1016/ j.amjmed.2003.12.018.

37. Posserud I, Agerforz P, Ekman R et al. Altered visceral perceptual and neuroendocrine response in patients with irritable bowel syndrome during mental stress. Gut 2004; 53(8): 1102–1108. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.017962.

38. Dishman RK, Berthoud HR, Booth FW et al. Neurobiology of exercise. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006; 14(3): 345–356. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.46.

39. Galper DI, Trivedi MH, Barlow CE et al. Inverse association between physical inactivity and mental health in men and women. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006; 38(1): 173–178. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000180883.32116.28.

40. Peters HPF, De Vries WR, Vanberge-Henegouwen GP et al. Potential benefits and hazards of physical activity and exercise on the gastrointestinal tract. Gut 2001; 48(3): 435–439. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.435.

41. De Schryver AM, Keulemans YC, Peters HP et al. Effects of regular physical activity on defecation pattern in middle-aged patients complaining of chronic constipation. Scand J Gastroenterology 2005; 40(4): 422–429. doi: 10.1080/00365520510011641.

42. Nunan D, Boughtflower J, Roberts NW et al. Physical activity for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochr Dat Syst Rev 2015; 1: CD011497. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011 497.