Laparoscopic repair of congenital paraesophageal hernia in an 18-month-old child – a clinical case and literature review

Matej Gura1, Barbora Špaková2, Marián Molnár2

+ Affiliation

Summary

Congenital paraesophageal hernia (CPEH) is an uncommon type of diaphragmatic hernia in the paediatric age. It can be asymptomatic, present with a variety of chronic gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms or complicated by acute gastric volvulus with strangulation in serious cases. Its rare occurrence and presentation with non-specific clinical features may delay the diagnosis. The principles of surgical treatment are generally well established with anti-reflux procedures included. Traditionally, surgery has been done using an open approach. Recently, laparoscopic repairs with encouraging outcomes have been reported. We present the case of an 18-month-old patient referred to an outpatient Clinic of Paediatric Surgery with incidental X-ray finding of CPEH type II confirmed by CT scan. The patient underwent an elective laparoscopy accompanied with Nissen fundoplication. According to our experience and literature review, we suggest laparoscopic repair of CPEH as an effective and safe method of treatment in infants and children.

Keywords

vrodená paraezofageálna hernia, laparoskopia, antirefluxná operácia

Paediatric gastroenterology and hepatology: case report

Introduction

Congenital paraesophageal hernia (CPEH) is a rare type of diaphragmatic hernia in the paediatric age [1–3]. It is assumed that CPEH has its origin in a defect remaining after the formation of the pleuroperitoneal membrane [4]. Hernias of the oesophageal hiatus are classified into four types [5]. Type I, or sliding hernia, involves herniation of the gastro-oesophageal junction (GEJ) and the gastric cardia only. The other three types are paraesophageal. In type II the GEJ remains fixed in the anatomic position and the gastric fundus serves as the lead point of herniation. The mobile components of the stomach subsequently migrate cephalad predominantly into the posterior mediastinum and middle or right extrapleural thoracic space [5,6]. Type III, mixed hernia, is a combination of both the previous types with intrathoracic displaced GEJ and herniation of the variable part of the stomach. Additional protrusion of other intra-abdominal organs occurs in type IV [2,5]. The term giant/massive paraesophageal hernia is used when more than 30% of the stomach migrates into the chest cavity [3].

CPEH may be diagnosed incidentally or may present itself by recurrent respiratory infections or vague gastrointestinal symptoms, predominantly gastro-oesophageal reflux (GER) [1,2,6–8]. Acute presentation by intrathoracic gastric volvulus or respiratory distress has also been reported [1,8–10]. Rare occurrence and presentation with non-specific clinical features may result in diagnostic pitfalls or treatment delay [1,11,12]. The basic principle of the surgical repair is to reduce the width of the hiatal defect and add an anti-reflux procedure. Traditionally, this has been done using conventional open approaches in children [2,6,13,14]. More recently, laparoscopic repairs have been reported [7,9,11,12,15,16]. We present the case of an 18-month-old toddler with incidentally identified CPEH type II managed successfully by laparoscopy.

Case report

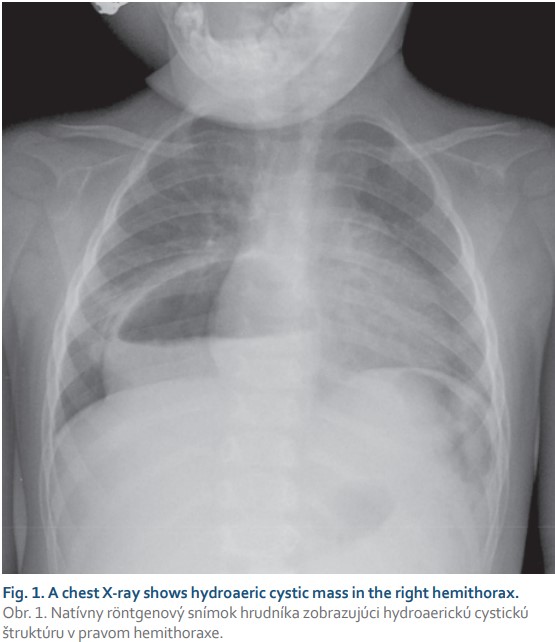

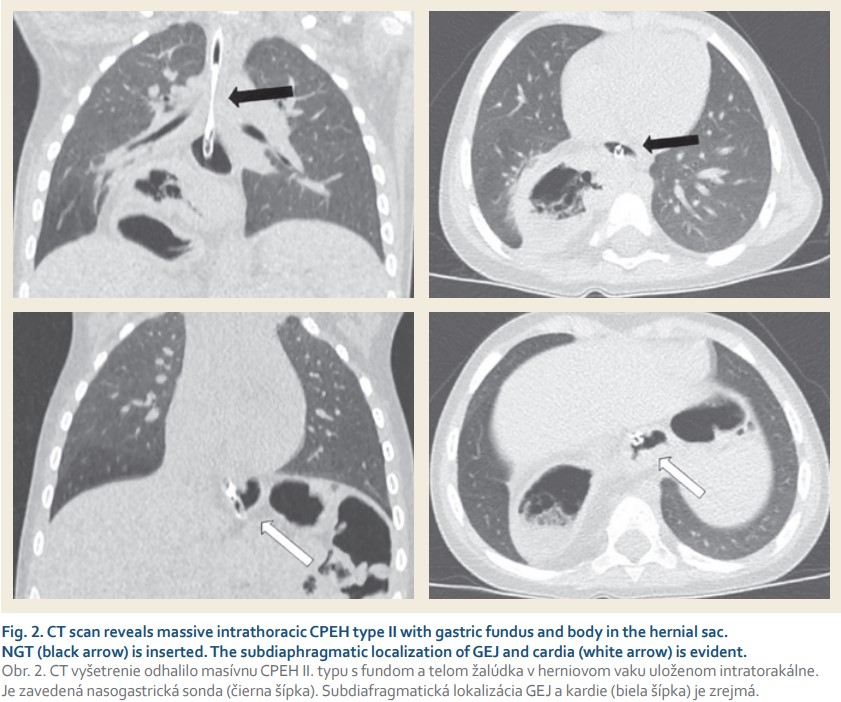

An 18-month-old female toddler was referred to our outpatient clinic after an incidental finding of hydroaeric cavitated mass in the right hemithorax on plain chest radiograph (Fig. 1) performed in the purpose of routine cardiologic control. The child was followed up by a paediatric gastroenterologist from 6 months of age because of GER suspicion, occasional postprandial abdominal discomfort with relieving regurgitation (1–2-times a month) and failure to thrive (weight and growth curve below the 3rd percentile). No accompanying respiratory symptoms were noticed. Concerning the patient’s history, the prenatal period, term delivery, postnatal adaptation and neonatal screening were uneventful. Apart from a cardiologic follow--up for patent foramen ovale no other pathology was identified. Prior to admission to our clinic, a CT scan showed a massive paraesophageal hiatus hernia type II with herniation of nearly the entire stomach into the right dorsal hemithorax (Fig. 2). GEJ with a nasogastric tube (NGT) was inserted and gastric cardia was identified in the anatomic position. The subsequent diagnostic process did not reveal any other associated anomalies. Laboratory tests were physiological and family history is negative for gastrointestinal diseases.

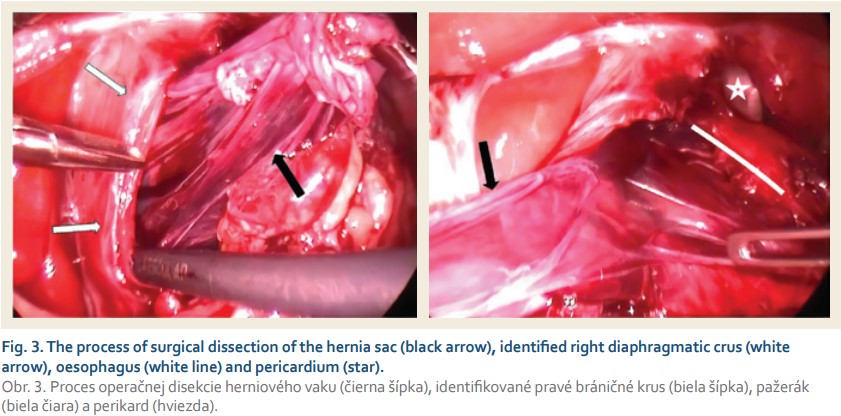

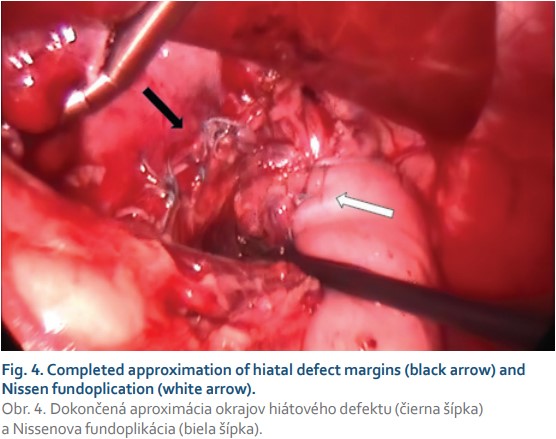

An elective operation was performed laparoscopically. Capnoperitoneum at 10 mmHg insufflated and 5 abdominal ports were placed. Intraoperatively, beyond the cardia the whole stomach herniating in the right dorsal mediastinum was reduced back into the abdomen. Subsequently the hernial sac was identified, dissected, detached from the pleura and excised in toto (Fig. 3). The right and left crus of the diaphragm were identified. The wide hiatal opening was then closed with 4–0 non-absorbable (Ethibond) interrupted sutures beginning at the dorsomedial site of the defect and ending around the oesophagus with 14 Fr NGT inserted intraluminally. Additionally, Nissen fundoplication was performed over the NGT in situ (Fig. 4). The intraoperative period was uneventful, with operative time 160 minutes. Epidural anaesthesia was administered intra- and postoperatively. The postoperative recovery was uncomplicated. Oral feeding was initiated on the 2nd postoperative day and the patient was discharged from the hospital on the 6th postoperative day. At the 2-month follow-up patient was well.

Discussion

Paraesophageal hernia is well known to occur in adults. In children, it typically occurs as an acquired complication of fundoplication or other procedures on the oesophageal hiatus, whereas the congenital form represents a rare entity [2,3,8]. The incidence of CPEH is estimated at 3.5–5% of all hiatal hernias [2,8]. The exact aetiology of CPEH is unknown. It is assumed that CPEH is secondary to embryonal developmental defect in the lumbar component of the diaphragm based on persistent right pneumoenteric recess [2,6]. Others have postulated that CPEH is due to laxity in gastric attachments and a deficient crura of diaphragmatic hiatus [1,9]. Most of the cases occur sporadically but there are reports of familial paraesophageal hernias, particularly among siblings, suggesting a genetic predisposition [6,17,18]. A high prevalence of concomitant anomalies, e. g. Marfan sydrome, chromosomal anomalies, malrotation and others have also been reported [1,2,13].

Paraesophageal hernias generally tend to enlarge with time [4,6]. The fundus and other parts of the stomach are pushed into the chest by positive intra-abdominal pressure and pulled up by the negative intrathoracic pressure [4,11]. During this cephalad migration, the stomach tends to rotate around its organoaxial axis – ‚upside-down stomach’, resulting in partial (chronic) or complete (acute) gastric obstruction [6]. Obstruction leading to gastric and/or oesophageal dilatation causes mediastinal shift and mass effect [1]. Acute gastric volvulus was associated with a paroaesophageal hernia in 7% of children [10]. Generally, the risk of the incarceration of the hernia leading to strangulation or perforation is approximately 5% [8]. In contrast, CPEH remains asymptomatic in 8% of all patients [2,6]. Acute clinical presentation may be associated with life-threatening complications such as incarceration, intrathoracic gastric volvulus with complete obstruction, gangrene, perforation and haematemesis, as well as acute respiratory distress [1,8,11,12]. In chronic presentation, recurrent respiratory infections can be observed accompanied by fever and attacks of coughing. Vague gastrointestinal signs and intermittent vomitus are usually present, especially in paraesophageal hernia type II [2]. Based on the high incidence of GER in CPEH, the symptoms may be attributed to the gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, common in this age group [1]. Chronic anaemia, feeding intolerance and failure to thrive may be other constitutional symptoms [4,8,11].

A chest X-ray followed by an upper gastrointestinal contrast study is a widely used diagnostic standard. However, a CT scan supports a definitive diagnosis, excludes other pulmonary or mediastinal aetiologies and defines the nature of the herniated content more accurately [3,6]. We recommend insertion of an NGT during CT, in order to help identify the position of the distal oesophagus and GEJ, thus distinguishing the type of hernia. Between the contrast study and CT only one modality should be utilised in order to prevent unnecessary radiation exposure [3]. The possibility of intermittent hernia reduction resulting in a negative chest X-ray can contribute to diagnostic delay [1]. In the absence of dysphagia, endoscopic examination is not compulsory [6].

Elective surgical repair is recommended in children with CPEH, even in asymptomatic cases because of potential life-threatening complications [1,2,6,11]. The surgical procedure is based on herniated content reduction, careful dissection with resection of the peritoneal sac, closure of the hiatal defect and an anti-reflux or fixation procedure. Complete hernial sac excision has been advocated in order to allow sufficient closure of the hiatus, thereby eliminating the risk of recurrence and cyst formation [19]. In the process of sac dissection and excision, the surgeon has to be aware of potential pericardial, pleural and mediastinal injuries [8]. Narrowing of the hiatus by crura approximation using a non-absorbable suture is a crucial part of the surgical treatment [1–3,7,11]. Care should be taken not to injure the dorsal vagus nerve, and crural approximation should not be too tight as this could lead to oesophageal obstruction and subsequent dysphagia [3]. The use of prosthetic material in children should always be avoided if possible [6,7]. If unable to perform tension-free crural approximation in wide defect, a mesh reinforcement can be considered [9].

According to current knowledge, GER is a common symptom within CPEH, i.e. in 50–68% of patients [2,3,14]. Moreover, the weakness of a phreno-oesophageal ligament, alteration of the angle of hiss, insufficient gastric ligamentous attachments, need for excessive dissection in crural region and intraoperative perioesophageal mobilisation increase the likelihood of GER development postoperatively [1,2,8]. The addition of an anti-reflux procedure is still controversial [1,8]. However, studies with the largest series of patients advocate anti-reflux fundoplication as an effective prevention of recurrence and postoperative GER development compared to procedures not including fundoplication [2,6,7,14]. The anti-reflux Nissen fundoplication performed laparoscopically has gained increased popularity because of its lower morbidity and shorter hospital stay when compared to the open procedure [8]. In children with CPEH it is the most frequently used method [3,7,9,16], followed by the Thal procedure [8,12,15]. Some surgeons try to decrease the risk of recurrence by gastropexy alone or additionally, fundoplication [11,13].

Laparoscopic repair of a paraesophageal hernia represents a routine surgical technique in adults [20]. In the paediatric group there is just one retrospective study of 28 children (including newborns) by Petrosyan et al assessing the laparoscopic approach [7]. According to this study, laparoscopic repair of CPEH supported by fundoplication is associated with low mortality (0% vs. 0–20%), decreased postoperative complications (3.5% vs. 22–30%) and a comparable long-term recurrence rate (7% vs. 5–11%) in comparison with the largest series of open approach [2,6,14], even in laparoscopic redo procedures. However, mortality strongly depends on the associated comorbidities [7]. In the study of Petrosyan et al the operative time averaged 125 min (range 61–247 min), when compared to 160 min in our case [7]. Other literature contains clinical cases or small case series (2–4 patients) describing laparoscopic treatment of CPEH in infants and children with authors prone to performing fundoplication (except one using gastropexy). All have reported a satisfying outcome overall [11,12,15,16], even in complicated forms of the disease [9]. Among these series the mean operative time was 158 ± 35 min and oral feeding resumed on the 1st or 2nd postoperative day in concordance with our case.

Concerning the anatomic site of the defect, we believe that the main advantage of laparoscopy lies in a magnified and detailed view of the crural and intrathoracic hernial sac area. In connection with the adjusted equipment it ensures ideal orientation and conditions for precise surgical work. The cosmesis aspect is also beneficial.

Conclusion

In conclusion, CPEH represents a rare diagnosis associated with various clinical presentations. CPEH has been traditionally operated by an open approach using laparotomy, thoracotomy or both methods simultaneously [2,6,14,18]. Despite it being technically challenging, recent advances in minimally invasive surgery have made it feasible and safe to repair CPEH laparoscopically in infants and children when performed by an experienced paediatric surgeon.

Submitted/ Doručené: 16. 4. 2021

Accepted/Prijaté: 17. 5. 2021

Matej Gura, MD

Clinic of Paediatric Surgery

Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin

Comenius University in Bratislava

Mala Hora 4A

036 01 Martin

Slovakia

matejgura@gmail.com

To read this article in full, please register for free on this website.

Benefits for subscribers

Benefits for logged users

Literature

1. Imamoğlu M, Cay A, Koşucu P et al. Congenital paraesophageal hiatal hernia: pitfalls in the diagnosis and treatment. J Pediatr Surg 2005; 40(7): 1128–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.03. 060

2. Yousef Y, Lemoine C, St-Vil D et al. Congenital paraesophageal hernia: the Montreal experience. J Pediatr Surg 2015; 50(9): 1462–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.01.007

3. Garvey EM, Ostlie DJ. Hiatal and paraesophageal hernia repair in pediatric patients. Semin Pediatr Surg 2017; 26(2): 61–66. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2017.02.008.

4. Patoulias D, Kalogirou M, Feidantsis T et al. Paraesophageal hernia as a cause of chronic asymptomatic anemia in a 6 years old boy; case report and review of the literature. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2017; 60(2): 76–81. doi: 10.14712/18059694.2017.97.

5. Kahrilas PJ, Kim HC, Pandolfino JE. Approaches to the diagnosis and grading of hiatal hernia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2008; 22(4): 601–616. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.12.007.

6. Karpelowsky JS, Wieselthaler N, Rode H. Primary paraesophageal hernia in children. J Pediatr Surg 2006; 41(9): 1588–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.05.020.

7. Petrosyan M, Shah AA, Chahine AA et al. Congenital paraesophageal hernia: Contemporary results and outcomes of laparoscopic approach to repair in symptomatic infants and children. J Pediatr Surg 2019; 54(7): 1346–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.07.008.

8. Al-Salem AH. Atlas of Pediatric Surgery: principles and treatment. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2020: 341–354.

9. Bradley T, Stephenson J, Drugas G et al. Laparoscopic management of neonatal paraesophageal hernia with intrathoracic gastric volvulus. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45(8): E21–E23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.05.033.

10. Cribbs RK, Gow KW, Wulkan ML. Gastric volvulus in infants and children. Pediatrics 2008; 122(3): e752–e762. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007- 3111.

11. Kundal AK, Zargar NU, Krishna A. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatus hernia in infancy. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2008; 13(4): 142–143. doi: 10.4103/0971-9261.44766

12. Bataineh ZA, Rousan LA, Abu Baker A et al. Congenital massive hiatus hernia type IV; initial experience with laparoscopic repair in young infant. Hernia 2014; 18(3): 427–429. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1222-z.

13. Jetley NK, Al-Assiri AH, Al Awadi D. Congenital para esophageal hernia: a 10 year experience from Saudi Arabia. Indian J Pediatr 2009; 76(5): 489–493. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0084-3.

14. Yazici M, Karaca I, Etensel B et al. Paraesophageal hiatal hernias in children. Dis Esophagus 2003; 16(3): 210–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1442- 2050.2003.00330.x.

15. van der Zee DC, Bax NM, Kramer WL et al. Laparoscopic management of a paraesophageal hernia with intrathoracic stomach in infants. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2001; 11(1): 52–54. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12193.

16. Yagi M, Nose K, Yamauchi K et al. Laparoscopic intervention for intrathoracic stomach in infants. Surg Endosc 2003; 17(10): 1636–1639. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8783-0.

17. Rees JE, Robertson S, McNinch AW. Congenital para-oesophageal hiatus hernia: an interesting family history. Emerg Med J 2004; 21(6): 749–750. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.007310.

18. Baglaj SM, Noblett HR. Paraoesophageal hernia in children: familial occurrence and review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int 1999; 15(2): 85–87. doi: 10.1007/s003830050522.

19. Watson DI, Davies N, Devitt PG. Importance of dissection of the hernial sac in laparoscopic surgery for large hiatal hernias. Arch Surg 1999; 134(10): 1069–1073. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.10.1069.

20. Latzko M, Borao F, Squillaro A et al. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernias. JSLS 2014; 18(3): e2014.00009. doi: 10.4293/ JSLS.2014.00009.