Liver cirrhosis in Roma patients from the perspective of the liver transplant centre

Světlana Adamcová Selčanová1, Radovan Takáč2, Jana Vnenčáková1, Daniela Žilinčanová1, Lukáš Lafférs3, Ľubomír Skladaný1

+ Affiliation

Summary

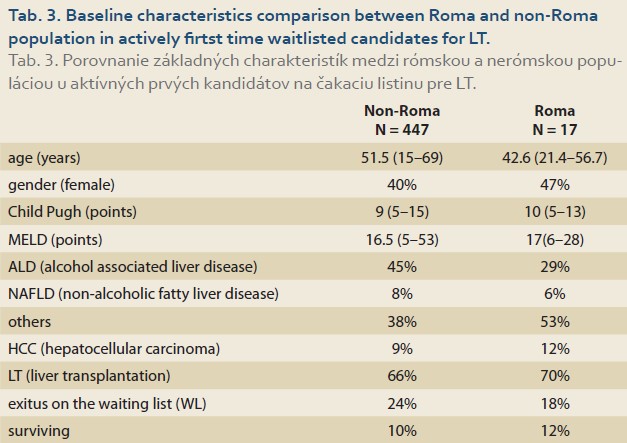

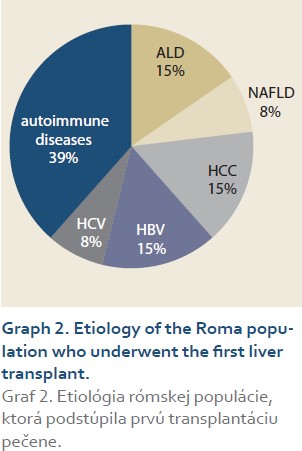

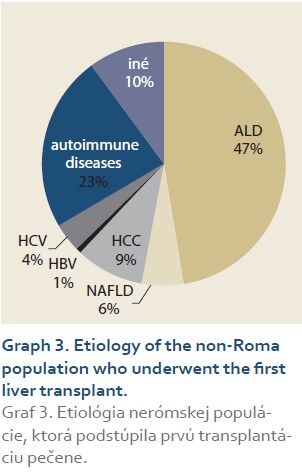

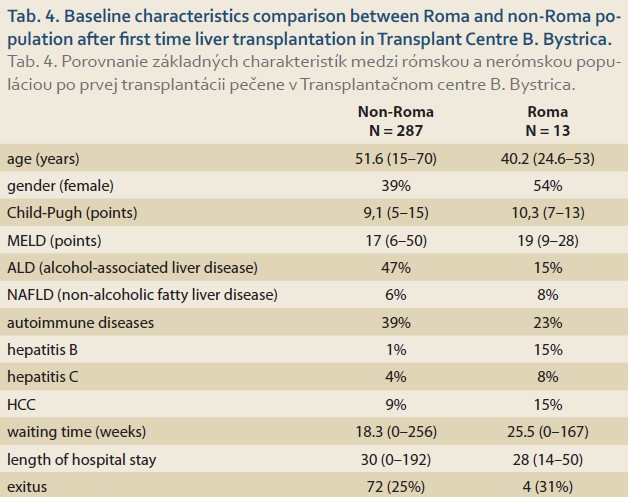

Introduction: Slovakia is a country with the highest prevalence of liver cirrhosis in the world and a country with the highest proportion of Roma ethnicity at the same time. However, there is only little evidence of Roma representation in national cohorts with cirrhosis. Aims: 1. To determine the prevalence of Roma ethnicity in our cirrhosis and liver transplant registers; to compare their 2. fundamental characteristics and 3. final results with patients from the majority population. Patients and methods: A retrospective study; we acquired data from 1. Cirrhosis registry RH7; 2. Liver transplant registry: a) patients listed active on the liver-transplant waiting list; b) patients underwent first LT. The first source – the cirrhosis registry RH7 (NCT 04767945; since 2014, RH7 has been listing consecutive patients admitted to hospital with liver cirrhosis). Up to 2021, the mode of the ethnicity determination was so-called “ascribed ethnicity”. The second source – the Liver transplant registry (since 2008); the mode of ethnicity determination was identical to the one of RH7. Apart from the ethnicity, the following points were recorded and analyzed in all patients: demographics, elementary cirrhosis-relevant clinical variables such as etiology and MELD score, as well as an elementary LT-relevant variables, such as waiting time and mortality. Results: We present the results on Roma ethnic group in three cohorts from two datasets, i.e. on 1,515 patients from RH7, on 464 waitlisted patients from LT registry and on 302 transplanted patients from LT registry, respectively. The representation of Roma ethnicity in these cohorts were 2%, 4%, and 4%, respectively. Significant differences in age and gender were detected in Roma cirrhotic patients: 46 vs. 55 years (P = 0.001) and female gender 25% vs. 39% (P = 0.042). Of the first time waitlisted candidates for LT, Roma patients were also significantly younger – 42.6 vs. 51.5 years; in addition, Romas had a less prevalent alcohol-associated etiology (ALD) and a more prevalent autoimmune etiology. Finally, Roma patients after first LT were younger – 40.2 vs. 51.6 years, again with lower etiology of ALD – 15% vs. 47% and more autoimmune etiology – 39% vs. 23%. The results of Romas from all cohorts in tertiary care were comparable. Conclusion: 1. the admission of Romas to a tertiary liver care is lower than expected, for unknown reasons; 2. the age of Romas entering tertiary care is approximately ten years lower; 3. the results of Romas in tertiary care is comparable to the majority population.

Keywords

liver cirrhosis, Roma ethnicity, tertiary liver care, waiting list, liver transplantation

Introduction

Slovakia is a country with the highest prevalence of liver cirrhosis in the world with the highest part of the Roma ethnicity at the same time [1]. Moreover, among young adults at the age of 25–45 years, liver disease is the number one cause of death [2]. However, there is only little evidence of Roma representation in national cohorts with cirrhosis.

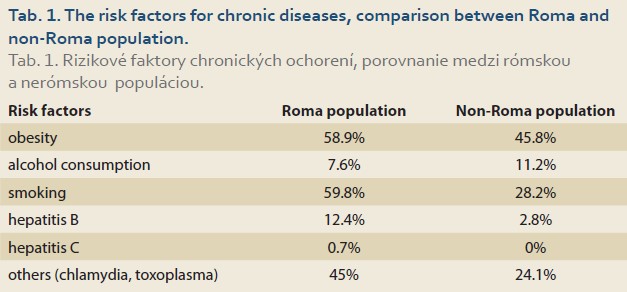

With 440,000 members in 2019, Roma ethnicity represents de facto 8% of the whole citizenship of Slovakia [3,4]. According to the available literature, we compared with the prevailing ethnicity of Slovakia (non-Roma), both the health status (morbidity) and the life expectancy of Romas are significantly worse [5–11]. In terms of the structure of morbidity and mortality, both acute (mostly infectious) and chronic diseases are responsible. In terms of the risk factors for chronic diseases, including the chronic liver diseases, data from Romas are available for obesity, smoking and alcohol consumption (Tab. 1) [12–18].

In addition to these factors, morbidity and mortality of Romas are worsened by various social determinants of health and health inequalities, such as poverty and education in general, food insecurity in particular, together with the housing, sanitary conditions, healthcare availability, seeking behaviour, health awareness, cultural preferences, fears, etc. [10,15,17–24].

Despite the efforts, such as HEPAMETA, to shed light on the liver health of Romas to the best of our knowledge, information on the prevalence and prognosis of liver cirrhosis are limited. To this end, as liver cirrhosis is becoming a major driver of national mortality, we decided to use two relevant datasets available at our tertiary liver unit: the liver transplant registry and the cirrhosis registry.

Aims

1. To determine the prevalence of Roma ethnicity in our cirrhosis and liver transplant registers; to compare their 2. baseline characteristics and 3. outcome to the patients from the majority population.

Patients and methods

We performed a retrospective registry study in which we obtained data from 1. the RH7 cirrhosis registry, and 2. the liver transplant registry, in which we addressed separately a) patients who were listed active on the liver-transplant waiting list, and b) patients who underwent their first LT. The first source – the cirrhosis registry RH7 (NCT 04767945) is operating since 2014 at the HEGITO tertiary liver unit; RH7 classifies a consecutive, consenting adults, admitted to hospital with liver cirrhosis. We excluded patients with an imminent death and malignancy other than transplantable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). This registry has been examined for ethnicity by two investigators (JV, DZ). The mode of the ethnicity determination was so-called ascribed ethnicity up to 2021. The second source – the liver transplant registry, is operating since 2008 and has been examined for ethnicity by SAS and RT; the mode of ethnicity determination was identical to the one of RH7. In addition to ethnicity, the followings were recorded and analyzed in all patients: demographics, elementary cirrhosis-relevant clinical variables such as etiology and MELD score, as well as an elementary LT-relevant variables such as waiting time and mortality.

For statistical analysis, we used legally obtained statistical software R – Pearson‘s Chi-squared test; Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; Fisher‘s exact test [25].

All the participants signed an informed consent before LT and agreed with the data publication. The study was carried out in accordance with the proceedings of the declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed an informed consent prior to anonymized data recording and agreed with data publication.

Results

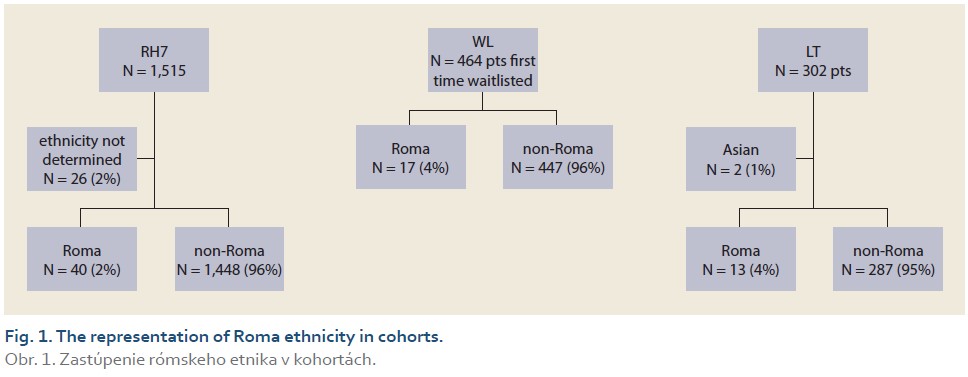

We are presenting results on the Roma ethnicity in three cohorts from two data sets, i.e. on 1,515 patients with cirrhosis from RH7, 464 waitlisted patients from LT registry, and 302 transplanted patients from LT registry, respectively (Fig. 1). Regarding our primary (null) hypothesis, at least 8% representation of Romas is assumed in all the three cohorts – i.e. patients with cirrhosis, patients active on the waiting list for LT, and patients after LT, our results point to the contrary: the representation of Roma ethnicity in these cohorts were 2%, 4%, and 4%, respectively. Of course, to calculate a statistical significance was not possible.

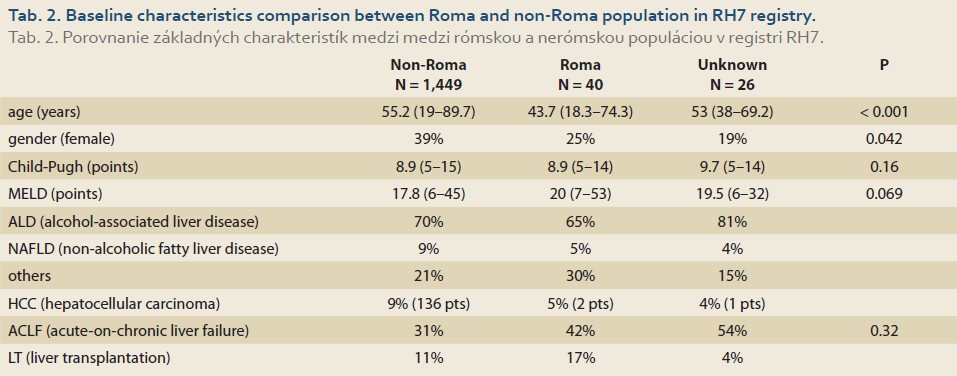

Significant differences of the Roma cirrhotics (as compared to those of non--Roma descents) were detected in two domains only – age and gender (Tab. 2): cirrhotics of the Romas were considerably younger (46 vs. 55, P = 0.001), with fewer females (25% vs. 39%, P = 0.042). The degree of decompensation according to the MELD score was greatly significant (17.8 vs. 20, P = 0.069).

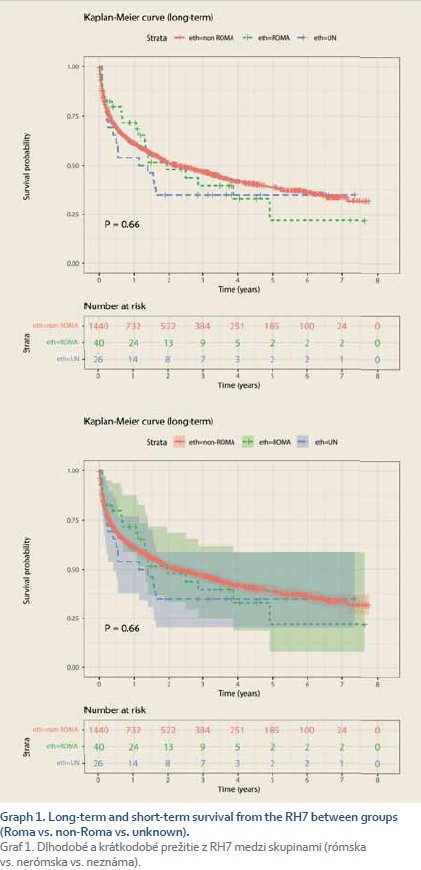

Furthermore, survival from the RH7 registration was not signifficantly different, although the Kaplan-Meier curves dissociated in short-term (up to one year) and in long-term (over 2 years) (Graph 1). Overall, it is important that the median survival of patients from RH7 is less than 2.5 years.

Out of the 464 actively first-time-listed candidates for LT, individuals representing the Roma ethnic group represented 4% (17 pts). Again, Roma patients were significantly younger than patients from the majority population (42.6 vs. 51.5 years); in addition, Romas had a less prevalent alcohol-associated etiology (ALD) of cirrhosis; and a more prevalent autoimmune etiology; otherwise, both ethnic subgroups were comparable in all recorded variables, including waiting-time, exclusion from the WL and achievement of LT (Tab. 3).

Finally, of the 302 patiens after their first LT, Romas represented 4% (13 pts). Compared to the majority population of LT patients, Romas were younger (40.2 vs. 51.6 years) with less alcoholic etiology (15% vs. 47%), more autoimmune etiology (39% vs. 23%), more hepatitis B etiology (15% vs. 1%) and more HCC etiology (15% vs. 9%) (Graphs 2, 3; Tab. 4).

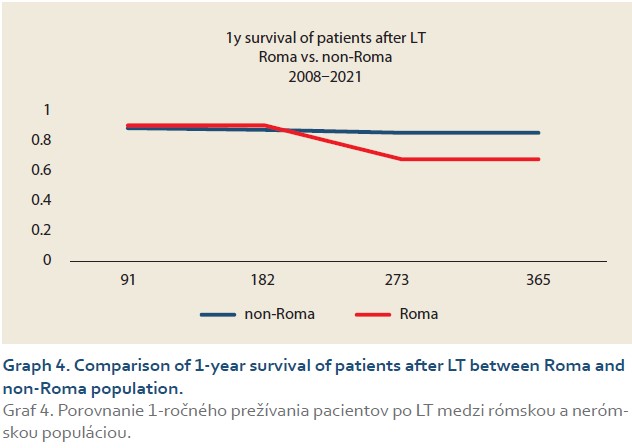

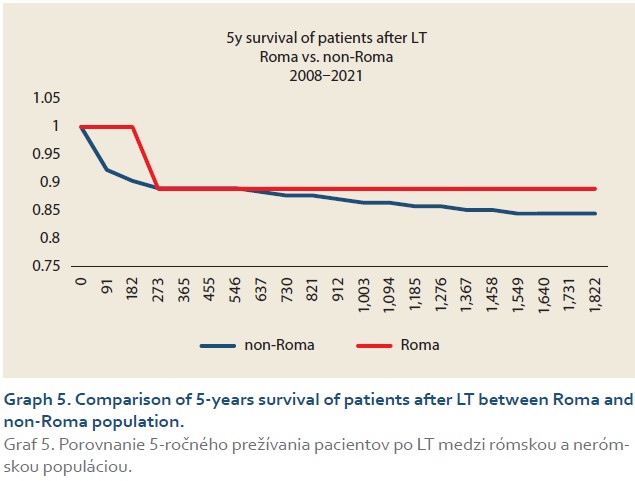

The outcome of transplanted Romas was comparable to the one of the majority population in the lenght of hospital stay after LT, as well as in matter of survival (Graphs 4, 5; Tab. 4).

Discussion

The main findings of our registry study were that i) Romas are underrepresented in the tertiary liver care, ii) Romas are ten years younger than non-Roma when reaching the end-stage of their chronic liver disease, iii) Romas are pre-selected for a referral to a tertiary liver care (by yet unknown subjective and objective mechanisms) and in case of tertiary liver care, iv) prognosis of Romas is comparable to the one of the majority population.

A question “why are Roma approximately ten years younger than non- -Roma patients in all the liver cohorts we analyzed”, cannot be answered based on our results. However, based on the results of other authors, one can speculate that this finding is a real reflection of the overall health status of Roma [5,7–14,17,18,20–24].

Roma suffer more from health-determing social inequalities, such as poverty, health literacy, access to healthcare, food insecurity/quality, etc.

Roma suffer from more risk factors of chronic diseases (implicitly including liver), such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, smoking, alcohol abuse, etc.

Roma suffer more explicitly from liver diseases, such as chronic hepatitis B.

Of course, the impact of sometimes catastrophic housing, homelessness, undiagnosed psychiatric illnesses, Roma-specific seeking behaviour based on fear and exclusion, etc., may also play an important role. However, these factors could not be solved using our datasets.

The main inspiration is the dynamics concerning gender representation in our three cohorts: the prevalence of females was lower, equal and higher in patients with cirrhosis on the waiting-list and after LT. The first hypothesis coming to mind is that males are detained in front of the door of tertiary care and LT for their more frequent toxic behaviour and non-compliance. Of course, there are other possible explanations – all beyond our study; however, they should be studied in further research.

It is very interesting to find ethnically associated diversity in the etiology of cirrhosis. Before we dive into the exciting possibility of a connection between the Roma ethnic group and autoimmunity, we need to go deeper. On the one hand, we need to find an ethnic-autoimmunity association with earlier stages of liver diseases in a larger cohort; we must examine the earlier stages of liver diseases (before tertiary care) for the proportion of ALD and NAFLD treated in the primary and/or secondary liver care. On the other hand, we must examine the literature on the subject of Roma-autoimmunity in rheumatology, immunology, etc.

A significantly higher MELD score while registering for RH7 might point to a delayed referral of Roma patients with cirrhosis to tertiary care. However, this notion has not been confirmed by comparable Child-Pugh and ACLF scores. For this reason, we are not entitled to draw any conclusions and we will keep this finding in the center of our further attention.

Another important result of our study – besides the proportion, age, gender and etiology domains – is more than reassuring domain of the outcome of our Roma patients. In the results, which serve as measures for controlling the quality of liver care, i.e. the availability of LT and survival, the results of Romas were comparable to the majority population. Specifically, there were no differences between Roma and non-Roma in RH7 and WL in terms of proportion of transplanted patients, neither were there any differences in survival in any of the three cohorts. Most likely, this means that after entering tertiary liver care, patients’ managment does not differ according to their ethnicity. For us providers, these results serve as an reassurance of our impartial approach to a person with liver cirrhosis.

Our study has had several limitations and strengths. The most important limitation is that the ethnicity has been assigned. We do not think that our results should be questioned for this reason. Instead, we need to blame our unintended ignorance of evolving legislation along with our temporarily limited field of vision – lacking a focus from the individual patient on ethnicity. Another limitation is the lack of RH7 data concerning the follow-up details after the discharge. As we are an hospital-based liver department, in RH7 we are left with the data obtained during the first hospital admission and we obtain the mortality data by our team from the national database of deceased citizens. Regarding the strengths of our study, in our opinion, two should be considered the most important – the very aim of our study and the large number of patients in RH7.

Conclusion

In comparison to the majority population of cirrhotics entering the tertiary liver care, our results lend support to the opinions that: i) the selection of Romas for a referral to the tertiary liver care is not the same, for unknown reasons; ii) the age of Romas entering the tertiary care is approximately ten years younger, for known reasons; iii) the outcome of Romas inside the tertiary care is comparable, for known reasons.

ORCID authors

Ľ. Skladaný ORCID 0000-0001-5171-3623,

S. Adamcová Selčanová ORCID 0000-0001-8181-1937,

J. Vnenčáková ORCID 0000-0001-9125-1662,

L. Lafférs ORCID 0000-0002-3141-3591.

Submitted/ Doručené: 19. 4. 2022

Accepted/Prijaté: 14. 6. 2022

Ľubomír Skladaný, MD, PhD

HEGITO (Division of Hepatology, Gastroenterology and Liver Transplantation)

FD Roosevelt Hospital

L. Svobodu 1 Square

975 17 Banska Bystrica

lubomir.skladany@gmail.com

To read this article in full, please register for free on this website.

Benefits for subscribers

Benefits for logged users

Literature

1. Wang PL, Flemming JA. Addressing the global cirrhosis epidemic: one size will not fit all. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5(3): 230–231. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30382-6.

2. Národné centrum zdravotníckych informácií. Zdravotnícka ročenka Slovenskej republiky 2018. [online]. Dostupné z: http: //www.nczisk.sk/Documents/rocenky/2018/Zdravotnicka_rocenka_Slovenskej_republiky_2018.pdf.

3. Tlačová správa k Atlasu rómskych komunít 2019 [online]. Úrad splnomocnenca vlády SR pre rómske komunity. Dostupné z: https: // www.minv.sk/?atlas-romskych-komunit-2019.

4. Atlas rómskych komunít na Slovensku 2019 [online]. Úrad splnomocnenca vlády SR pre rómske komunity. Dostupné z: https: //www.minv.sk/?atlas-romskych-komunit-2019.

5. Šupínová M, Hegyi L, Klement C. Zdravotný stav Rómov na Slovensku. Hygiena 2015; 60(3): 116–119. doi: 10.21101/hygiena.a1334.

6. European Commission. Country Report Slovakia 2018. [online]. Dostupné z: https: //ec.europa.eu/info/publications/2018-european-semester-country-reports_en.

7. Belak A, Geckova AM, van Dijk JP et al. Why don’t segregated Roma do more for their health? An explanatory framework from anethnographic study in Slovakia. Int J Public Health 2018; 63(9): 1123–1131. doi: 10.1007/s00038-018-1134-2.

8. Belak A, Geckova AM, van Dijk JP et al. Health-endangering everyday settings and practices in a rural segregated Roma settlement in Slovakia: a descriptive summary from an exploratory longitudinal case study. BMC Public Health 2017; 17(1): 128. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4029-x.

9. Belak A, Veselska ZD, Geckova AM et al. How well do health-mediation programs address the determinants of the poor health status of Roma? A longitudinal case study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14(12): 1569. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14121569.

10. Šprocha B, Bleha B. Mortality, health status and self perception of health in Slovak Roma communities. Soc Indicat Res 2021; 153(4): 1–22. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02533-2.

11. New Eastern Europe. Real and imagined problems of the Roma community in Slovakia. 2016 [online]. Available from: https: //neweasterneurope.eu/2016/07/12/real-and-imagined-problems-of-the-roma-community-in-slovakia/.

12. Macejova Z, Kristian P, Janicko M et al. The Roma population living in segregated settlements in Eastern Slovakia has a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, kidney disease, viral hepatitis B and E, and some parasitic diseases compared to the majority population. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17(9): 3112. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093112.

13. Babinská I, Madarasová Gecková A, Jarcuska P et al. Does the population living in Roma settlements differ in physical activity, smoking and alcohol consumption from the majority population in Slovakia? Cent Eur J Public Health 2014; 22(Suppl): 22–27. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3897.

14. Fedacko J, Pella D, Jarcuska P et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in relation to metabolic syndrome in the Roma population compared with the non-Roma population in the eastern part of Slovakia. Cent Eur J Public Health 2014; 22 Suppl: 69–74. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3904.

15. Bartošovič I, Hegyi L. Zdravotné problémy rómskeho etnika. Lekársky obzor 2010: 4.

16. Jarcuska P, Bobakova D, Uhrin J et al. Are barriers in accessing health services in the Roma population associated with worse health status among Roma? Int J Public Health 2013; 58(3): 427–434. doi: 10.1007/s00038-013-0451-8.

17. Paraličová Z, Jarčuška P, Hudáčková D. Infekčné choroby u marginalizovaných skupín Rómov žijúcich v osadách. Via Pract 2015; 12(3): 111–113.

18. Popper M, Szeghy P, Šarkozy Š. Rómska populácia a zdravie: analýza situácie na Slovensku. 2009 [online]. Dostupné z: http: //www.gitanos.org/upload/13/60/Eslovaquia-corrected.pdf.

19. Bojko M, Hidas S, Machlica G et al. Inklúzia Rómov je potrebná aj v zdravotníctve. 2018 [online]. Dostupné z: www.mfsr.sk/files/archiv/34/2018_23_Inkluzia_zdravie_final.pdf.

20. Bastos JL, Celeste RK, Faerstein E et al. Racial discrimination and health: a systematic review of scales with focus on their psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 2010; 70(7): 1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.020.

21. Kolarcik P, Madarasova Geckova A, Orosova O et al. Deliquent and aggressive behaviour among Roma and non-Roma adolescents. Eur J Public Health 2009; 19 Supp1: 237.

22. Kolarcik P, Madarasova Geckova A, Orosova O et al. To what extent does socioeconomic status explain differences in health between Roma and non-Roma adolescents in Slovakia? Soc Sci Med 2009; 68(7): 1279–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.044.

23. Kolarcik P, Madarasova Geckova A, Orosova O et al. Predictors of health-endangering behaviour among Roma and non-Roma adolescents in Slovakia by gender. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010; 64(12): 1043–1048. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.092098.

24. Skodova Z, van Dijk JP, Nagyova I et al. Psychosocial factors of coronary heart disease and quality of life among Roma coronary patients: a study matched by socioeconomic position. Int J Public Health 2010; 55(5): 373–380. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0153-4.

25. R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2021 [online]. Dostupné z: https: //www.R-project.org/.